Contents

Questo articolo è disponibile anche in:

When talking about Italians, the Italian Peninsula is not the only one worth mentioning. The inextricable links of history have bound Bel Paese with another peninsula far from the Mediterranean coasts. We are talking about Crimea, the region much disputed in recent years between Moscow and Kiev. A few hundred Italian-Crimeans still remain here today, extremely proud of their roots. Their history has long been unfairly doomed to oblivion despite their remarkable role in the history of Crimea.

An ancient presence

Relations between Crimea and Italy have their roots in antiquity. You have to go back a couple of millennia to see the first irrefutable archaeological finds testifying to an Italic presence. The ancient Kingdom of the Cimmerian Bosphorus arose in Crimea, a client state of the Roman Empire starting from the 1st century AD. The most important cities of this Hellenic kingdom thrived around the Kerch Strait, the only passage to reach the Sea of Azov.

This geographical area was a fundamental commercial foothold for the Romans, the fulcrum of economic exchanges with the peoples of the endless Sarmatian plains. The political submission of the kingdom present there also allowed Rome to have absolute control over the Pontus Euxine (Black Sea). As today, Crimea was the key to dominance over this important sea. The fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 a.D. only marked a temporary end of the Italian presence in this area.

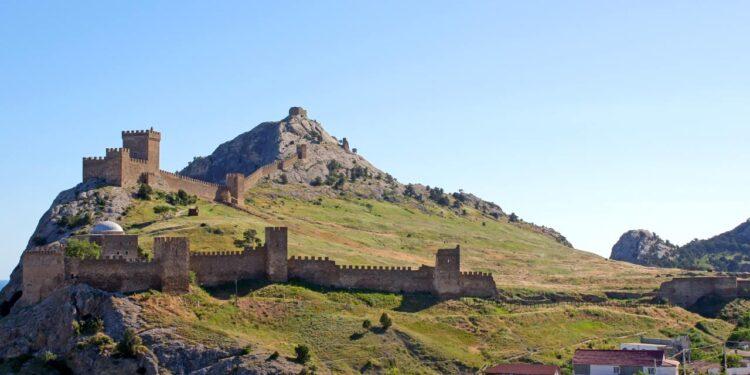

After about 800 years, the two main maritime cities of Venice and Genoa once again appeared on the Crimean coasts. The two republics were determined to establish strong trading outposts that would allow them to do business with the Russian-Tatar world. After an initial Venetian presence following the sack of Constantinople in 1204, the Genoese ousted their bitter enemies in 1261. Here the Superba created eleven commercial bases, four of which were fortified: Cembalo (Balaklava), Soldaia (Soudak), Caffa (Feodosia) and Vosporo (Kerch).

Credits: East Journal.

These fortresses served as a solid shield for Genoese trade in the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov, on which the Genoese held the notable emporium of Tana (near present-day Rostov-on-Don). The Genoese period was a generally prosperous time for southern Crimea. Many Ligurians settled there and the area was also frequented by other Italian merchants. This peripheral area of Europe was also unknowingly the origin of the most disastrous event for the Middle Ages of the Old Continent.

In the 14th century, Caffa was besieged by the Tatars of the Golden Horde who, frustrated by the tenacious Genoese resistance, tried the card of bacteriological warfare. The corpses of the soldiers who died from disease were thrown inside the city walls, causing a plague epidemic. The besiegers failed to conquer the city, but the besieged were still forced to flee due to the plague. The Genoese ships thus ended up transporting the plague germ to Genoa and, from there, throughout Europe.

Credits: Wikipedia.

The regional balance was broken in the 15th century, when the tragic fall of Constantinople in 1453 presaged the unstoppable rise of the Ottoman Empire. In fact, just over twenty years later, Mehmet II proceeded with the conquest of all the Genoese strongholds, starting a long period of Turkish domination. The Ottoman invasion was a huge tragedy for the Genoese. Many perished or were enslaved, others managed to return to their homeland, some took refuge in Ukraine or Circassia.

Some lucky and tough farmers and inhabitants of Italian origin did not abandon Crimea, but their number was now small. Over the course of a hundred years, this caused their assimilation into the new dominant Tatar-Ottoman culture. For the second time in history the thread that connected Bel Paese to Crimea was abruptly severed. But this interruption was not as definitive: the rise of the Russian Empire would once again allow several Italians to seek their fortune here.

The Italians of Crimea from Catherine the Great to the October Revolution

The crushing defeats suffered by the Ottomans in the eighteenth century at the hands of the Austrians and Russians started the progressive process of downsizing of the Sublime Porte throughout Europe. Crimea was soon the target of Russian expansionism, always projected towards the warm southern seas. The Russian-Ottoman war of 1768-1774 and that of 1787-1792 decreed the Russian conquest of the current Ukrainian coasts and the Crimean peninsula.

It is precisely at this moment that the conditions for a new Italian immigration were created. This was favored by Catherine the Great’s need to repopulate Crimea, tested by the long years of war. This initial project attracted Corsicans, Genoese, Sardinians and Tuscans. However, this attempt was unsuccessful, pushing the first settlers to return to their native lands or disperse into neighboring territories. New Italian migratory flows occurred following the Napoleonic wars.

In 1820 there were now 30 Italian families living there originating from multiple regions. From 1830 until the beginning of the 20th century, new groups settled in Crimea, joining those pioneer families already present since the beginning of the century. It is precisely from these communities that the current remaining Crimean Italians descend. Their origins were mainly Apulian, Ligurian and Campanian, of agricultural and sailor social extraction.

Soon, however, even more specialized individuals such as architects, notaries, doctors and artists swelled the Italian-speaking community. The arrival of the Italians was favored by Tsar Nicholas I himself also in the light of the growing agreement between the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies and the Russian Empire in the mid-19th century. The city of Kerch became the center with the largest number of Italians, but Feodosia (ancient Caffa) and Simferopoli were also affected by the rebirth of Italian-speaking communities.

The Italian presence is still symbolized today by the Catholic Church of Santa Maria Assunta of Kerch built between 1831 and 1845, in neoclassical style, financed and built entirely by the city community. It is nowadays still popularly known as “the church of the Italians”. Furthermore, it is precisely in this period that the two main pre-unification Italian states, the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies and the Kingdom of Sardinia, opened their own consulate in Kerch.

Credits: Wikipedia.

On the eve of the First World War, the Italian community in the province of Kerch amounted to 2% of the entire population according to Russian census data. Its growth rate was very high, so much so that some Italian-Crimeans even moved outside of Crimea to join the “sister” Italian communities also present in other Black Sea cities such as Odessa, Mariupol, Donetsk, Batumi and Novorossiysk.

Before the advent of the Bolsheviks, Kerch had an Italian primary school, a library, a meeting room and an Italian cultural club. Furthermore, the local newspaper Kerchensky Rabochij regularly published articles written in the Italian language. The sociopolitical conditions for the Crimean Italians were, however, once again on the verge of being swept away. The wind of the October Revolution was starting to whip along the coasts of the ancient Genoese cities.

From the Soviet extermination to Vladimir Putin

The new Soviet elite began to care about the Italian-Crimeans starting from the mid-1920s. They were viewed with suspicion, as potential conspirators and sympathizers of fascism which was consolidating in Italy in those years. It was therefore decided to proceed with a “re-education” of the minority through the introduction of anti-fascist Italian exiles who would monitor the actions and intentions of the Italian-Crimeans, also doing their utmost to busily spread the ideals of socialism.

We proceeded with the closure of the church of Santa Maria Assunta, so as to repress the religious sentiment of the faithful. Furthermore, in light of the forced collectivisation of the countryside, the Italians were ordered to create “Sacco e Vanzetti” kolkhoz (collective farm). Anyone who was against this new practice was destined either for exile or arrest. The effects of the new Soviet course were not long in arriving. By the mid-1930s, Italians had already fallen to 1.3% of the inhabitants of the Kerch province.

But the Italian repression was only just beginning. The consolidation of Stalin’s political practice did not even spare Crimea. The purges initiated by the Georgian dictator between 1935 and 1938 caused many Italians to disappear into thin air, accused either of pro-fascism or of espionage. The extermination work finally reached its peak in the night between 29th and 30th January 1942 in which almost all Italians, including anti-fascists, were deported to Kazakhstan. The charges were of collaboration with the enemy. The German army had temporarily occupied Kerch in November, before the Soviets retook the city.

This was enough for the Soviet authorities to justify the forced displacement of the entire Italian-speaking population. Those who had escaped the January deportation were tracked down and captured in February to go through the same fate. The journey to the Kazakh steppes was exhausting and lasted for two months. Once they arrived in the Kazakh desert, the Italians had to endure night temperatures between -30 and -40 degrees. Many women and children could not survive such adverse conditions and the most resistant succumbed after years in detention camps.

Credits: Dook International.

According to official data from the Soviet Interior Ministry, only 460 Italians managed to see Crimea again following the de-Stalinization pursued by Khrushchev. Some preferred to settle in the Kazakh steppes, now terrified of the idea of being recognized as Italians. In fact, even many of the lucky few to return to Crimea began to live in secret, by Russifying their name and preserving their identity only within their most intimate circles.

The Italians of Crimea today number approximately 300, gathered around CERKIO association (Community of Emigrants in the Crimean Region – Italians of Origin) which does its utmost to preserve the identity of the Italian-Crimeans, promote their history and consolidate their relationships with Italy. The community still preserves many Italian sayings and expressions in speech, although only very few are able to express themselves fluently in the Italian language. Nonetheless, the sense of belonging to a distinct ethnic-cultural group is strong in every member.

Following the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014, the Italian-Crimeans officially obtained justice, being recognized as a “Crimean minority persecuted by Stalinism” by the will of Russian President Vladimir Putin on 12 September 2015. The historic decision was taken during a meeting in Yalta between Silvio Berlusconi, the president of CERKIO association Giulia Giacchetti Boico and Vladimir Putin. The strong friendship between the former Italian president and his Russian counterpart certainly played an important role in the success of the initiative.

Credits: Reuters.

Yet, the Italians of Crimea still remain ignored and looked at with distrust by the State that should consider them as brothers: the Italian Republic. In fact, many requests for citizenship made by the Italian-Crimean community have fallen on deaf ears. Despite the attested Italian descent of these people, Rome has proven reluctant to listen to them.

This unacceptable behavior on the part of the Italian institutions must be rectified, since they are called to defend and honor anyone who has the pride and real will to affirm their Italianness on behalf of their descent. This is even more relevant for those who paid with their blood just to be able to say: “Я итальянец; I am Italian”.