Contents

Questo articolo è disponibile anche in:

‘Abd al-Malik was probably one of the most important caliphs of the Umayyad dynasty, and one of the best remembered. He ascended the throne in 685 and ruled until 705, the year of his death. During his long reign, he initiated several reforms for the consolidation of the new caliphate entity, directing enormous efforts toward its Islamization and Arabization.

About the Umayyad dynasty

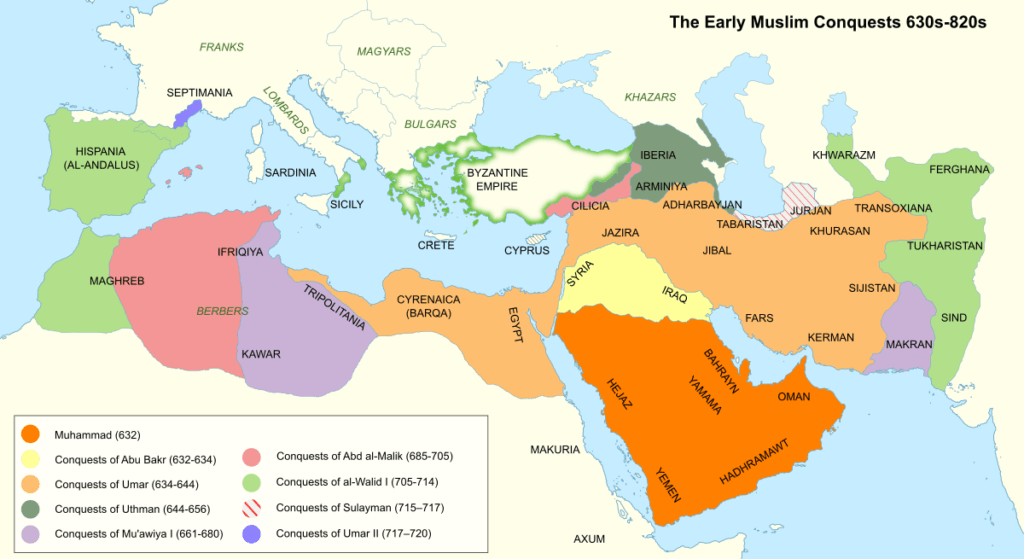

The Umayyad Caliphate was short, but intense. It was founded in 661 AD at the hands of Mu’awiya, who became the first caliph of the Banū Umayya dynasty, but was overthrown just under a century later, in 750, by the Abbasid power. During the Umayyad reign, Arab expansion reached its historical peak. The conquests, already begun in the golden period of the first caliphate, that of the four “well-guided” (the rashidūn), continued both in the East and in the West, from Samarkand to the Iberian Peninsula.

Source: Amitchell125 (Wikimedia Commons); licenza: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.en

In succession, 14 members of the Banū Umayya clan assumed power, divided into two branches: the Sufyanids and the Marwanids. They reigned in Damascus, the capital of the new caliphate, previously located in Medina, and thanks to the Syrian army, they were able to increase their power. Among the main reasons for the Umayyad success, in fact, the military expansion was crucial, leading to the conquest of vast territories and the ability to cope with two civil wars (in Arabic, fitna) which changed the fate of the Islamic world forever.

Furthermore, thanks to the Umayyad caliphs, important architectures, such as the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem and the Great Mosque of Damascus, were built, and impetus was given, although to a lesser extent than the subsequent Abbasid rulers, to progress in the scientific and medical fields. The caliphs also promoted the circulation and preservation of culture through the translation of manuscripts into Arabic.

The great caliph ‘Abd al-Malik

‘Abd al-Malik was the second caliph of the Marwanid Umayyad dynasty. He devoted his twenty-year reign to the administrative organization of the Arab Empire, the reunification of the Caliphate, and the suppression of internal opposition, marking the pinnacle of Umayyad power and prosperity.

Despite his religious interests and ideals, also evidenced by his surnames: Amīr al-muʾminīn (Prince of believers) and Khalīfat Allāh (Caliph or vicar of God), ‘Abd al-Malik was also a skilled politician. During the first half of his reign, he faced a civil war against his rival Zubayr, the self-proclaimed caliph in the Hijaz region, and faced some local revolts in Syria, Egypt, and Palestine. He emerged victorious: Zubayr was defeated in 692 and the revolts were repressed. Thanks to the triumphs of ‘Abd al-Malik, the Islamic community could thus be reunited once again.

The merits of the Khalifa cover many other areas, not just political ones. Among his major reforms, mention should be made of the coinage of the first Islamic currency, the implementation of an efficient postal system (barīd), aiming at keeping the Caliph informed on his vast reign, the construction and restoration of communication routes, especially between Damascus and Palestine, and the impulse given to architecture.

The Arabization policy

Many of the reforms implemented by ‘Abd al-Malik had a strong symbolic impact on the affirmation of the Arab-Islamic identity of the reign. Among his first actions, the Arabization of the Umayyad administration played a central role. Through a decree, the Khalifa established that the official language in the documents of the empire should be Arabic and that all papers and registers written in Coptic, Greek, Persian, Hebrew, and Aramaic should be translated into the language of the Sacred Koran. Arabic, therefore, became the official language of the empire.

Arab centrality was also emphasized through the adoption of a new monetary system with inscriptions in Arabic characters. The new coinage signaled the birth of a new power, with its own identity, and sent a silent signal of challenge to the powerful Byzantium, whose currency was widely distributed.

So, Arabic became the language par excellence of the empire, but its presence did not take root everywhere as expected. The case of the Iranian territory is emblematic because, despite the imposition of the Arabic alphabet, inhabitants still preserved their Persian language. Actually, years later, around the 10th century, Neo-Persian would emerge as the language of the masterpieces of Iranian literature by Ferdowsī and other great poets.

The construction of Islamic identity

‘Abd al-Malik represented a turning point in the history of Islam. Thanks to him, the new monotheism strengthened its identity, starting with the Koran. He made available to the Islamic umma (community) a new and definitive “edition” of the Sacred Book, improved through the addition of diacritical points (the dots of the Arabic letters) and the complete vocalization of its verses. The Khalifa entrusted the task of finalizing this “second edition” of the Koran to his designed governor of Hijaz and Iraq, namely, al-Hajjāj.

The Umayyad caliph must also be credited with having emphasized the role of the Prophet Muhammad. The hadīth, that is, the sayings and deeds of the Prophet, began to be collected and organized in the Sunna during his reign. Compared to Christianity and Judaism, Islam, therefore, differed from the other religions of the Book due to the emphasis placed on the mission of Muhammad, the last of the Prophets sent to earth by God.

The theme of the unity and uniqueness of God, a common cornerstone of all three monotheisms, was further modified through the double testimony of faith (the shahāda, one of the pillars of Islam) addressed both to God and to his messenger Muhammad. Starting from the reign of ‘Abd al-Malik, the followers of the new religion were not identified simply as “believers” (in Arabic: mu’min), but as “Muslims” (muslim), referring to those who believed both in God and in the prophecy of Muhammad.

The Dome of the Rock

Among the architectural monuments erected during the caliphate of ‘Abd al-Malik, the Dome of the Rock (Qubbat al-Sakhra, in Arabic) is of irrefutable importance. It is one of the first Islamic buildings ever built, a symbol of the victory of the third monotheism over the older religions. The sanctuary, built in 691 AD, is located in the Temple Mount in Jerusalem and is an architectural work of refined beauty, with intense blue Byzantine mosaics and a solemn gold dome.

The monument presents a peculiarity that lies in its partial tie with all three religions of the Book (Judaism, Christianity and Islam). Firstly, the Dome of the Rock cannot be called a mosque stricto sensu. The plan of the octagonal building refers, in fact, to the resurrection, to the Christian martyrium. Nevertheless, it is neither a Christian building, since it contains inscriptions of Qur’anic passages that reject the idea of the trinity. Secondly, the place where it stands, Mount Moriah, also plays an important role for Judaism, since in the Torah it is written that the Final Judgment will originate there.

The sanctuary, however, remains an Islamic symbol. It is the place where, as described in the Koran, Muhammad’s ascension into heaven (isrā’) occurred. Some scholars have reason to believe that ‘Abd al-Malik conceived the Dome of the Rock as a monument-symbol of victory over Christians and Jews within a common religious context, Jerusalem, home of the most ancient Abrahamic faiths.

In conclusion, the caliphate of ‘Abd al-Malik was a moment of transition, fundamental for the history of Islam which defined part of its identity, especially through the relevance given to the Prophet Muhammad.

Stay up to date by following us on Telegram and Instagram!