Contents

Questo articolo è disponibile anche in:

“Tripoli, bel suol d’amore” (Tripoli, beautiful soil of love), so went a popular Italian song from the early 20th century, telling of a virgin and prosperous Libya. In reality, such prosperity was not within reach but hidden under years of necessary hard work. Libya went from a nominal Ottoman territory to an Italian colony in revolt up to the flagship of Italian colonialism in less than thirty years.

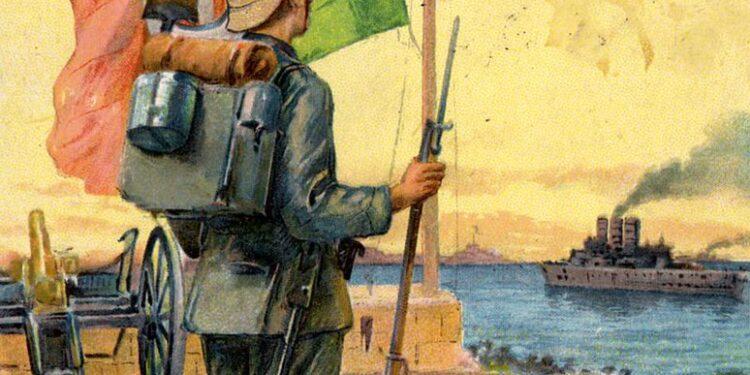

The great proletarian has moved: the Italian-Turkish War

The history of Italian Libya began with the Italian-Turkish War which broke out in September 1911. For a good deal of Italian politicians, this conflict represented an important test that a united Italy was called upon to overcome. The invasion was anticipated by months of propaganda and heated political clashes. Libya had been portrayed as a defenseless land rich in resources by nationalists and some liberals.

Italian public opinion in the early twentieth century was still marked by the defeat of Adua in 1896. The Italian defeat against the Ethiopians of Menelik II had fallen on the Bel Paese as a true humiliation. The rest of Europe had judged Italy as a nation still too young and inexperienced. All this was also peppered with offensive and denigrating comments about the country’s war spirit. The Italians’ pride had been wounded and the desire for revenge was strong in many men of the time.

Opposition to the colonial plans in Libya arose only from socialist circles, although even within these there were voices who professed to be enthusiastic about the military deed. It was now clear: Italy would land in Libya, declaring war on the “sick man of Europe”, the Ottoman Empire. After a round of consultations with the other European powers, Giolitti had obtained a guarantee that the Italian action would not cause any disagreement with the other European states.

The invasion opened with a simple and effective plan: the Libyan ports of Tripoli, Benghazi, Derna and Tobruk were occupied by the troops of the Royal Army, escorted by the Navy. The weak Turkish fortifications were quickly destroyed by the Italian gunboats, facilitating the landing of the infantrymen. The news of the first victorious actions caused waves of enthusiasm throughout the country.

Pascoli expressed his utter support for the enterprise with his famous speech “The great proletarian has moved“. The famous scholar saw Libya as a land in which to channel national emigration and follow in the footsteps of Ancient Rome. According to the poet, Italian society was intrinsically proletarian and popular, placing itself in antithesis to the “bourgeois” empires of Great Britain and France.

Among the various lieutenants who took part in the enterprise there was also young Giovanni Messe, future Marshal of Italy. The Apulian officer perfectly described in his war diary the impressions and sensations of the Italian soldiers about to disembark on the Libyan coast. Tripoli appeared like a white oasis surrounded by African sands, whose lines were interrupted by tall minarets.

The Royal Army landed without any resistance in the future Libyan capital. Messe himself was amazed at the initial welcome he received from the local population. This situation, however, did not last long. The Ottoman strategy would be based on guerrilla warfare carried out by rapid mounted units, in the light of the sheer Italian superiority in any field. The desert nature of Libya along with Turkish skirmishes forced the Italians to establish a front line only outside the occupied coastal cities.

The metropolitan troops were assisted for the first time by contingents of Eritrean and Somali askaris who were landed as reinforcements at a later time. Meanwhile, the Ottoman counterattack began to intensify and on 23 October a force of 10,000 Ottoman and Arab soldiers charged the defensive line of Tripoli. This was the precursor to Sciara Sciat massacre. The speed of the mounted units got the better of a contingent of five hundred Bersaglieri on the right wing of the Italian deployment.

About half of these were forced to surrender, heading towards a sad and macabre fate. The Ottoman-Turkish troops tortured and massacred the captured Bersaglieri, seventeen of whom were crucified at Sciara Sciat oasis. The rest of the Italian forces did not stand idly by, quickly managing to recover lost ground. For the poor Bersaglieri, however, it was already too late. The terrible death of these comrades triggered the desire for revenge throughout the Italian ranks. Sciarra Sciat massacre was avenged the following day with extreme violence. Several hundred natives were executed in Mechiya oasis.

Credits: Inchiesta Online.

Similar events proved the exacerbation of the conflict and the duality of the Libyan people: the inhabitants of the coast tended to collaborate with the Italians, while those inland rebelled violently. The latter joined the jihad launched against the Christian invader, joining the ranks of the Ottoman skirmish. As is known, wars are always a vector of innovation. The Italian-Turkish war was not an exception to this rule as evidenced by the first aerial bombing in history by lieutenant Gavotti on 1 November 1911.

During these first aerial bombardments, future father of Turkey Mustafa Kemal, engaged in the defense of Derna, was injured. Despite fierce resistance, Italian efforts prevailed. Between January and August 1912, Italy secured control of the entire Libyan coast. The invasion of the Dodecanese and the outbreak of the First Balkan War forced the sultan to accept an armistice and sign the Treaty of Lausanne. The Ottoman Empire was officially defeated, but Libya was not yet pacified. The Libyan guerrillas would offer fierce resistance to the new authority in Rome.

The Sword: Rodolfo Graziani and Pietro Badoglio

The pacification of Libya was a tortuous and difficult process. The outbreak of the First World War and Italy’s entry into the war in May 1915 nullified the efforts made up until that moment. The coastal strip remained under Italian control, while the desert and plateaus became the focus of Libyan resistance. In the Fezzan territories, groups of Turkish soldiers commanded by Enver Pasha continued the fight. The new colony necessarily had to be reconquered.

The new war effort began in 1921. Logistics was the first major problem that the Italian High Command found itself facing. The desert nature of internal Libya made the supply line extremely stretched and subject to potential attacks by fast-moving Libyan guerrilla units. The surprise effect and the geographical conformation were further important factors in favor of local resistance.

Italy used Air Force extensively. Thanks to the information provided by the aviators via radio and the use of Eritrean askaris, supported by armored cars and units of meharisti (camel troops), the Italians made their way into Fezzan. It is in this scenario that Rodolfo Graziani, one of the most famous Italian generals of the Ventennio, operated. The reconquest of Tripolitana was completed, as was the conquest of Fezzan between 1929 and 1930.

Credits: Wikipedia.

Cyrenaica proved to be much less easily penetrable. It was the birthplace of Libyan partisan commander Omar al-Mukhtar, known as the “Lion of the Desert”. Al-Mukhtar became the leading figure of the Libyan resistance, capable of keeping the Italian forces in check even after Tripolitana and Fezzan were solidly in Rome’s hands. Pietro Badoglio was appointed governor of Tripolitana and Cyrenaica in 1928, with the aim of speeding up repression operations.

Badoglio chose aforementioned Graziani as field commander. The general from Lazio immediately worked for the victory of the Italian troops, quickly understanding the reasons for the success of the local guerrillas. In fact, al-Mukhtar’s men acted quickly, carrying out the “hit and run” tactic, and then retreated to the Saharan lands that were difficult for Italian troops to access. The nomadic and semi-nomadic peoples of Cyrenaica served as the mainstay of al-Mukhtar’s strategy. These treated wounded soldiers as well as replenished the ranks if necessary and smuggled weapons and materials through Egypt.

Credits: Wikipedia.

However, the resistance was not supported by all the Libyan people. The inhabitants of the coasts agreed to collaborate with Italy. These were regarded as traitors by Al-Mukhtar and his acolytes. Punitive expeditions aimed at attacking any collaborative action were widespread on the coast. Rome immediately understood that the key to pacifying the region was to gain the favor of the population. Badoglio in fact did his utmost to grant amnesty to those who decided to collaborate with the Royal Army.

In the meantime, Graziani gave further vigor to the rapid war strategy, massively using the agile colonial troops of Eritrea and Libya. The carrot policy could not fail to be matched by that of the stick. In 1930 Badoglio chose to divide the civilian population from the rebel bands. Graziani initiated the deportation of 100,000 locals from the Gebel plateau so as to relocate them to detention camps near Benghazi. Many died from overcrowding and poor sanitary conditions.

This brutal policy had the desired effects as most of the population loyal to al-Mukhtar had now been deported. The Libyan forces were greatly weakened, paving the way for the occupation of Kufra oasis in January 1931. Graziani exploited the favorable moment by implementing further pressure on the enemy. Two hundred and seventy kilometers of the Libyan-Egyptian border were sealed by a line of barbed wire, patrolled by Italian units.

Supplies to the Libyans could no longer pass through. Omar al-Mukhtar, surrounded and alone, was found by Italian planes in September 1931 and captured. The resistance leader was hanged in Soluch, after a summary trial, on the 16th of the same month. By January 1932, the Libyan resistance was now completely defeated and Badoglio solemnly announced the success of the military operations and the definitive pacification of the colony.

The strategy of pursuing the Libyan militias and separating the civilian population had proved successful, according to Omar al-Mukhtar himself. Libya was now under the full control. Much blood had been shed and the weapons now had to give way to the plough.

The Plough: Italo Balbo

Italo Balbo embodied a new chapter of Italian domination for Libya. A man with great charisma, he was a war veteran, legendary aviator, as well as a fascist party official. His fame and his tendency towards decision-making autonomy led him to be appointed governor of the colonies of Tripolitania, Fezzan and Cyrenaica. One of his very first acts as governor was the unification of the three Libyan colonies into one in 1934, namely Italian Libya.

Mussolini thus initiated a new policy and narrative of Libya, decreeing the Libyan Arabs “Italian Muslims and the Fourth Shore of Italy“. These words were followed by the granting of second-class citizenship, which guaranteed various rights to the indigenous population in accordance with Koranic law. The Italian academic environment of the time proved to be extremely far-sighted in identifying Islam as a force that would later be central to contemporary geopolitics.

Many Italian intellectuals pushed for an “Italian imperial awareness” towards the Arab-Islamic world. This axiom had to be based on Italy’s natural push towards the East, Arabia and the Indian Sea. Italy had, therefore, to promote the valorisation and meeting between the European Christian world and the Eastern Islamic world, so as to cultivate a spirit of friendship between the two souls of the Mediterranean.

Credits: Wikipedia.

Concepts such as “Italy’s ability to become an empire” and “Italy as a guide and bridge between Europe, the Mediterranean and the East” became rather debated. Balbo was a front-line promoter of these ideas. The Ferrarese definitively closed several detention camps dating back to the Gebel deportation wanted by Badoglio. New Koranic schools were opened and the young people belonging to the Arab Youth of Littorio were guaranteed the learning of Arabic and Italian. Ancient Roman cities such as Leptis Magna and Sabratha were also rediscovered and restored, symbols of the ancient past that linked Libya to Italy.

After the first three years of Balbo’s governorship, Mussolini decided to go on an official visit to Libya in 1937. This event was extremely symbolic as the Duce proclaimed himself “protector of Islam“, while wielding the sword of Islam on horseback. Mussolini was therefore trying to legitimize himself as a “caliph”. Mussolini’s claim was not a groundless action. The Ottoman sultan, in fact, had held the title of caliph since 1516, the year of the Ottoman conquest of Mamluk Egypt).

Italy had defeated the Ottoman Empire in 1912 and, following the birth of the Republic of Turkey, the title of caliph was vacant. This action had a certain propagandistic echo among Muslim intellectual centers. Libya underwent a major construction program, including bridges, schools, hospitals and roads. The Via Balbia, connecting the Libyan coastal strip from the Tunisian border to the Egyptian one, represented the flagship of the Italian modernization work.

Sporting events such as the Tripoli Grand Prix saw the light. Aviation also marked Libya’s belonging to the Italian Empire. The Fourth Shore of Italy was in fact united to the motherland and the other colonies by the Empire Line of Ala Littoria, with weekly flights from Rome to Benghazi. New villages were also built for the Berber and Libyan inhabitants, however Italian immigration was favored.

Libyan city centers grew very quickly thanks to the immigration of Italian settlers. In 1939, approximately 35% of the inhabitants of Tripoli and Benghazi were Italian. This conciliatory and participatory policy saw a partial regression in the wake of the new racial laws. Libyan citizenship was made more restrictive, further highlighting the differences between Italians and Libyans. This particularly irritated Balbo, who considered the Arabs as a people deserving of respect.

An excerpt from his “Fascist social policy towards the Arabs of Libya” summarizes his thought:

“We will not have rulers and dominated in Libya, but Catholic Italians and Muslim Italians, one another united by the enviable fate of being the constructive elements of a powerful great organism, the Fascist Empire.“

The reflections on the future of Libya were in any case swept away with Italy’s entry into the war in June 1940. Balbo had sided against Mussolini’s interventionist decision, suggesting the Duce to avoid direct involvement in the conflict. The war ultimately proved fatal even for the Air Marshal himself. Balbo was mistakenly shot down on June 28th by Italian anti-aircraft fire from Tobruch, being mistaken for one of the English bombers that had attempted to attack the Italian positions shortly before.

The end of the Italian period in Libya was marked in 1942 following the English advance in North Africa. The toil, dreams, hopes, words and ideas that had animated Libya in those years were thus buried under the sand of the desert like ancient Roman ruins.

Stay up to date by following us on Telegram and Instagram!